Untangling Ancient India's Caste System: A Deep Dive

The Varna system, a foundational concept, significantly influenced what is the caste system in ancient india, shaping social hierarchies. Brahmanical texts, as authoritative sources, offer interpretations of this hierarchical structure. The impact of this social stratification on regions like the Indus Valley Civilization continues to be a subject of scholarly inquiry. Understanding what is the caste system in ancient india requires analyzing these interconnected elements to grasp its complex historical development and societal implications.

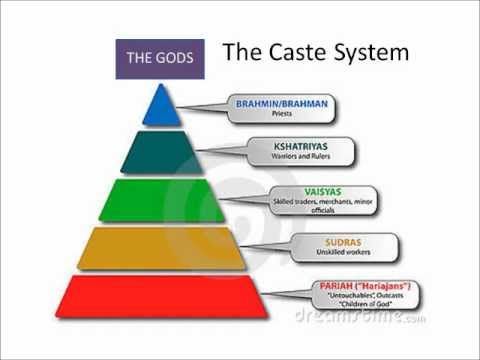

Image taken from the YouTube channel RTHS History Dept. (RTHS History) , from the video titled The Caste System and Ancient Indian Society .

The caste system in ancient India stands as a profoundly influential and intricate framework of social stratification. It's a system that has shaped the lives of countless individuals over millennia. At its core, the caste system is a hierarchical arrangement that dictates social standing, occupation, and interactions based on birth.

It is far from a simple division; it is a multifaceted construct with deep historical roots and enduring consequences.

A Brief Overview of Caste

The caste system in ancient India can be defined as a hierarchical social structure, which divided society into distinct groups based on birth. These groups determined an individual’s occupation, social status, and access to resources.

The system's origins are debated, but its presence is evident in ancient texts and archaeological findings. The significance of understanding the caste system lies in its pervasive influence on Indian history, culture, and social dynamics.

It affected everything from religious practices to political power structures.

Complexity and Enduring Legacy

One cannot overstate the complexity of the caste system. It isn't just a matter of a few broad categories. Instead, it encompasses a vast network of sub-castes and localized variations.

This intricate web has made it both resilient and challenging to dismantle.

The enduring legacy of the caste system continues to reverberate in contemporary India, despite legal prohibitions and social reforms. Its impact is visible in areas such as marriage, employment, and political representation.

Understanding this legacy is vital for comprehending modern Indian society and its ongoing struggles with equality and social justice.

Historical Context and Geographical Scope

The historical context of the caste system dates back to ancient India, with its roots potentially traceable to the Vedic period (c. 1500-500 BCE). Over centuries, it evolved and solidified, influenced by religious beliefs, social norms, and political power structures.

The geographical scope of the caste system was primarily the Indian subcontinent. While its influence extended to neighboring regions, its most pronounced impact was within the borders of what is now India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal.

Within this vast region, the caste system manifested in diverse ways, adapting to local customs and traditions.

The enduring legacy of the caste system continues to reverberate in contemporary India, despite legal prohibitions and social reforms. Its impact is visible in areas such as marriage, employment, and political representation. Understanding this legacy is vital for comprehending modern Indian society and its ongoing struggles with equality and social justice. To fully grasp the complexities of this system, it's crucial to first examine the theoretical framework that underpinned it: the Varna system.

The Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Varnas

The Varna system represents the foundational, albeit theoretical, framework upon which the ancient Indian caste system was constructed. It provided a conceptual blueprint for organizing society, although the practical reality, as we will see later, often diverged significantly.

The Four Varnas: A Hierarchical Division

The Varna system posits a four-tiered social structure, each Varna with its own prescribed roles, responsibilities, and inherent status. These Varnas, in descending order of social standing, are: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras.

Brahmins: The Priestly Class

At the apex of the social hierarchy were the Brahmins. They were primarily the priestly class, scholars, and teachers.

Their responsibilities encompassed performing religious rituals, studying and teaching the sacred texts (the Vedas), and guiding the spiritual life of the community. Brahmins were considered the custodians of knowledge and held immense social and religious authority.

Kshatriyas: Warriors and Rulers

The Kshatriyas occupied the second tier of the Varna system. They were the warriors, rulers, and administrators of society.

Their Dharma (duty) was to protect the people, maintain law and order, and govern the territory under their control. Kshatriyas were expected to be courageous, skilled in warfare, and upholders of justice.

Vaishyas: Merchants and Agriculturalists

The Vaishyas constituted the third Varna. They were primarily merchants, agriculturalists, and traders.

Their main function was to engage in economic activities, such as farming, cattle rearing, and commerce. The Vaishyas were responsible for providing the economic sustenance of society.

Shudras: Laborers and Service Providers

At the bottom of the Varna hierarchy were the Shudras. They were mainly laborers and service providers.

Their primary role was to serve the other three Varnas by performing manual labor, providing essential services, and supporting the overall functioning of society. Shudras were often denied access to education and religious rituals.

Hierarchy and Inherent Inequalities

The Varna system was inherently hierarchical, with each Varna assigned a specific position and corresponding privileges or disadvantages. This hierarchical structure was not merely a division of labor; it also embedded significant inequalities.

The higher Varnas enjoyed greater access to resources, power, and social status, while the lower Varnas faced systemic discrimination and limited opportunities. This inherent inequality was a defining characteristic of the Varna system, shaping social interactions and perpetuating social stratification for centuries.

The Varna system provided a theoretical framework, but the everyday reality of the caste system was far more nuanced and complex. This is where the concept of Jatis comes into play, representing the practical units through which the system operated.

The Practical Reality: Jatis, Sub-Castes, and Occupation

While the Varna system offered a broad, four-fold classification of society, the actual lived experience of individuals was determined by their membership in a Jati. These Jatis were far more numerous than the Varnas, often numbering in the thousands across the Indian subcontinent.

Jatis: The Building Blocks of Caste Society

Jatis can be understood as sub-castes or kinship-based occupational groups. They were the primary units of social organization, dictating an individual's social standing, occupation, and marriage prospects. Unlike the Varnas, which were relatively fixed and immutable, Jatis exhibited a degree of fluidity, with new ones emerging over time due to factors such as migration, occupational specialization, or religious conversion.

The Intricate Web of Jati Affiliations

Each Jati possessed its own distinct customs, traditions, and rules of conduct. These rules governed various aspects of life, including diet, dress, rituals, and interactions with members of other Jatis. Jati councils, known as panchayats, played a significant role in enforcing these norms and resolving disputes within the community.

Occupation: A Defining Feature of Jati Identity

One of the most significant aspects of the Jati system was its close association with occupation. Traditionally, individuals were expected to follow the occupation associated with their Jati.

This hereditary occupational structure reinforced the social hierarchy, with certain Jatis being associated with prestigious or economically advantageous occupations, while others were relegated to menial or ritually polluting tasks.

Over time, occupational specialization led to the formation of new Jatis, as groups of artisans, craftsmen, or traders branched off from existing ones. This intricate web of occupational Jatis contributed to the remarkable diversity of Indian society.

Localized Diversity and the Proliferation of Sub-Castes

The Jati system was characterized by its localized nature and the sheer number of sub-castes. Each region of India possessed its own unique configuration of Jatis, reflecting local economic conditions, social structures, and cultural traditions. The number of Jatis varied significantly from region to region, but even within a single area, there could be dozens or even hundreds of distinct Jati groups.

This localized diversity made it difficult to generalize about the Jati system as a whole. What held true for one Jati in one region might not apply to another Jati in a different part of the country.

Endogamy: Maintaining Boundaries and Preserving Purity

Endogamy, the practice of marrying within one's own Jati, was a cornerstone of the caste system. It served to maintain the boundaries between Jatis, preserve the purity of lineage, and prevent the dilution of occupational skills and knowledge.

Marriages were typically arranged within the Jati, with parents playing a key role in selecting suitable partners for their children. Inter-caste marriages were strongly discouraged, and in some cases, even punishable by expulsion from the Jati.

The rigid enforcement of endogamy ensured that the Jati system remained intact for centuries, despite facing challenges from social reformers and religious movements. It solidified the hierarchical structure and limited opportunities for social mobility.

The hereditary occupational structure inherent in the Jati system wasn't merely a matter of economic convenience; it was deeply ingrained in the cultural and religious fabric of ancient India. This brings us to the powerful role played by scripture, law, and social norms in solidifying the caste system's grip on society, shaping individual destinies and collective consciousness.

Scripture, Law, and Social Norms: Reinforcing the Caste System

Ancient Indian society wasn't solely structured by practical realities on the ground; the caste system was also deeply legitimized and reinforced through religious texts, legal codes, and pervasive social expectations. These elements worked in concert to create a framework that not only justified but also perpetuated the hierarchical divisions within society.

The Scriptural Foundation: Varnas in Ancient Texts

Early Vedic texts offer some of the earliest glimpses into the conceptual origins of the Varna system. While not explicitly detailing the rigid structure that would later characterize the caste system, these scriptures provided a foundational narrative that would be built upon and interpreted over centuries.

One key passage, the Purusha Sukta in the Rigveda, describes the creation of the four Varnas from the body of a primordial being. This creation myth, though symbolic, provided a divine origin for the social hierarchy, lending it an aura of inevitability and righteousness.

It's crucial to note that the interpretation of these early texts evolved considerably over time. The initial, perhaps more fluid, understanding of Varna gradually solidified into the rigid caste system that defined much of ancient Indian society.

Dharma and the Justification of Caste Duties

The concept of Dharma played a central role in reinforcing the caste system. Dharma, often translated as duty or righteousness, prescribed specific roles and responsibilities for individuals based on their Varna and Jati.

Each caste had its unique Dharma, a set of obligations and codes of conduct that were considered essential for maintaining social order and cosmic balance. Fulfilling one's Dharma was not merely a social expectation but a religious imperative.

By adhering to their caste-specific duties, individuals were believed to be contributing to the overall well-being of society and progressing on their spiritual path. This ideology provided a powerful justification for the inequalities inherent in the caste system, as each group was seen as playing a necessary role in the grand scheme of things.

The Manu Smriti: Codifying Caste Rules

Perhaps the most explicit and influential text in codifying the caste system was the Manu Smriti (also known as the Laws of Manu). This ancient legal text outlined detailed rules and regulations governing various aspects of social life, with a particular focus on reinforcing caste hierarchies.

The Manu Smriti prescribed different sets of laws and punishments for individuals based on their caste, solidifying the unequal treatment inherent in the system. It dictated rules regarding marriage, occupation, diet, and social interaction, all designed to maintain the purity and separation of the different castes.

The text also emphasized the importance of endogamy (marriage within one's own caste) as a means of preserving caste boundaries. Furthermore, it outlined strict penalties for those who violated caste norms, reinforcing the system's authority and discouraging social mobility.

While the Manu Smriti's influence has been debated and challenged over time, its impact on shaping social attitudes and legal practices related to caste is undeniable. It served as a powerful tool for legitimizing and perpetuating the caste system for centuries.

Scripture, law, and social norms, therefore, played a critical role in codifying and entrenching the caste system within the societal framework. However, the full extent of this system's reach can only be understood when we consider those who were relegated to the margins, existing entirely outside the prescribed Varna structure.

The Oppressed: Untouchables (Dalits/Scheduled Castes) - Outside the Varna System

The caste system's hierarchy didn't just define the roles and responsibilities within the four Varnas; it also determined who was excluded altogether. Those deemed "Untouchable," now often referred to as Dalits or Scheduled Castes, occupied the lowest rung of the social ladder – or, more accurately, existed entirely outside of it. Their plight represents perhaps the most egregious aspect of the caste system, characterized by severe social discrimination and profound dehumanization.

The Concept of "Untouchability"

"Untouchability" was a social construct rooted in notions of purity and pollution. Certain groups were deemed inherently impure, and physical contact with them was believed to defile members of the higher castes. This belief system resulted in widespread segregation, denial of basic rights, and forced labor.

Dalits were often excluded from temples, schools, and other public spaces. They were forced to live in segregated settlements, often located on the outskirts of villages and towns. Access to wells and other sources of water was frequently denied.

Even their shadows were considered polluting by some. This pervasive discrimination permeated every aspect of their lives, trapping them in a cycle of poverty and social exclusion.

Social Implications and Discrimination

The social implications of untouchability were devastating. Dalits were denied basic human dignity and treated as subhuman. They were subjected to verbal abuse, physical violence, and systematic oppression.

The denial of education and economic opportunities further entrenched their marginalized status. They were denied access to justice and had little or no recourse against discrimination and abuse.

This pervasive system of social control served to maintain the existing power structures and reinforce the dominance of the upper castes. The weight of these social constraints shaped not only their daily lives, but also their sense of self-worth and potential.

Occupations Assigned to the "Untouchables"

One of the most significant aspects of untouchability was its connection to specific occupations. Dalits were typically assigned tasks considered ritually polluting or degrading by the upper castes.

These occupations often included:

- Manual scavenging: Cleaning toilets and disposing of human waste.

- Leatherworking: Handling animal carcasses and tanning hides.

- Sweeping: Cleaning streets and public spaces.

- Cremation: Working at cremation grounds.

These occupations were not only physically demanding and hazardous, but also carried a significant social stigma. The association with these tasks further reinforced the perception of Dalits as impure and deserving of their marginalized status. The imposed occupational structure served to reinforce their social and economic subjugation, perpetuating the cycle of caste-based discrimination.

The pervasive influence of caste extended into nearly every facet of life, dictating not only occupation and social standing, but also severely limiting opportunities for upward mobility. While the system was designed to maintain a rigid social hierarchy, history reveals that it wasn't entirely impermeable.

Social Mobility and Change: Limited Opportunities

The caste system, at its core, was a deeply entrenched structure designed to limit social mobility. The Varna and Jati classifications were typically hereditary, meaning that one's birth largely determined their social standing and occupational destiny.

This system presented formidable barriers to individuals or groups seeking to improve their position within society.

Restrictions on Social Mobility

The restrictions on social mobility within the caste system were multifaceted and deeply ingrained.

Dharma, the concept of duty and righteousness, played a key role in reinforcing the system. Individuals were expected to adhere to the roles and responsibilities associated with their caste, discouraging any attempts to transgress these boundaries.

Social norms and expectations further solidified the rigidity of the system. Inter-caste marriage was largely prohibited, and social interactions between different castes were often limited or discouraged.

These restrictions were not merely social customs; they were often codified in legal and religious texts, lending them an air of legitimacy and permanence. The Manu Smriti, for example, outlines strict rules and regulations concerning caste, further limiting the scope for social fluidity.

Glimmers of Hope: Instances of Social Mobility

Despite the inherent rigidity of the caste system, historical records and scholarly analysis suggest that social mobility, while limited, was not entirely absent.

Political and Economic Factors

Instances of upward mobility occasionally arose due to political or economic shifts. A successful military leader from a lower caste, for instance, might accumulate enough power and influence to challenge the existing social order and elevate their own status and that of their community.

Similarly, a particularly skilled artisan or merchant from a lower Jati might gain economic prosperity, allowing them to improve their social standing.

It's important to note that such instances were relatively rare and often met with resistance from the higher castes. Any upward mobility was typically a slow and gradual process, often spanning generations.

Collective Mobility

Sometimes, an entire Jati might experience a change in social status through a process known as "Sanskritization," a term coined by sociologist M.N. Srinivas.

This involved the adoption of customs, rituals, and practices of the higher castes by a lower caste, often over a prolonged period, in an attempt to claim a higher social standing.

Sanskritization, however, did not necessarily translate into full acceptance by the higher castes, and the process could often be fraught with social tensions.

The Gupta Period: An Era of Relative Social Stability

The Gupta period (c. 320-550 CE) is often considered a golden age in Indian history, characterized by political stability, economic prosperity, and cultural flourishing.

However, from the perspective of social mobility, the Gupta era was marked by relative social stability.

The existing caste system was largely maintained, and there is limited evidence to suggest significant upward or downward mobility during this time.

The Gupta rulers generally upheld the existing social order, and the Varna system continued to be the dominant framework for social organization.

While the Gupta period witnessed advancements in various fields, it did not bring about significant changes in the fundamental structure of the caste system. Social mobility remained limited, and the vast majority of the population continued to be bound by the hereditary nature of their caste.

Video: Untangling Ancient India's Caste System: A Deep Dive

FAQs: Untangling the Ancient Indian Caste System

[This section addresses common questions about the complexities of the ancient Indian caste system, aiming to provide clarity on its origins, structure, and impact.]

What were the core divisions within ancient India's caste system?

The ancient Indian caste system was primarily divided into four main categories known as varnas: Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (merchants and traders), and Shudras (laborers and service providers). Outside this varna system were those considered "untouchable", later known as Dalits, who performed tasks considered ritually impure.

How did the ancient caste system impact daily life?

The varna you were born into determined many aspects of your life in ancient India. This included your occupation, social interactions, marriage prospects, and even dietary habits. Movement between varnas was generally not permitted, creating a rigid social hierarchy.

What is the caste system in ancient India, and what was its religious basis?

The caste system in ancient India, known as varna, was a hierarchical social stratification. Though not explicitly laid out as such, some believe that it was justified by interpretations of Hindu scriptures, particularly the Purusha Sukta hymn in the Rigveda, which describes the origin of the varnas from the body of a cosmic being. This provided a religious framework to support the social divisions.

Did everyone in ancient India accept the caste system?

While the caste system was a deeply ingrained part of ancient Indian society, there is evidence of resistance and dissent. Various religious and philosophical movements challenged the varna system, advocating for social equality and spiritual liberation regardless of caste. This suggests that not everyone accepted the rigid social hierarchy.